Thom Nickels

Contributing Editor

Philadelphia’s most famous cultural observer, writer Camille Pagilia, author of the classic Sexual Personae, writes that “Poetry began in ancient ritual as rhythmic chanting, and its early history was intertwined with music and dance. It belonged to the oral tradition for millennia until the invention of writing. After that, the visual format of the poem on the page became intrinsic to its identity.”

Two classic poets who were educated in Philadelphia but who then went on to move to other cities were Hilda Doolittle, or H.D. and Marianne Moore.

Early photographs of the poet Hilda Doolittle show an elegant young woman who, in many ways, resembled actress Glenda Jackson in Ken Russell’s 1989 film, Women in Love.

Born in 1886 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to a father who was a University of Pennsylvania astronomy professor, and a mother who was a pious Moravian, Doolittle at 15 was, according to poet William Carlos Williams, “…tall, blond, with a long jaw and gay blue eyes.”

In 1895, the family moved to Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, where her mother’s religious beliefs (in Moravian theology, all souls are female, and Christ is the husband of the male, as well as of the female), began to form the foundation of young Hilda’s growing poetic consciousness and eventual attraction to ancient Greek culture.

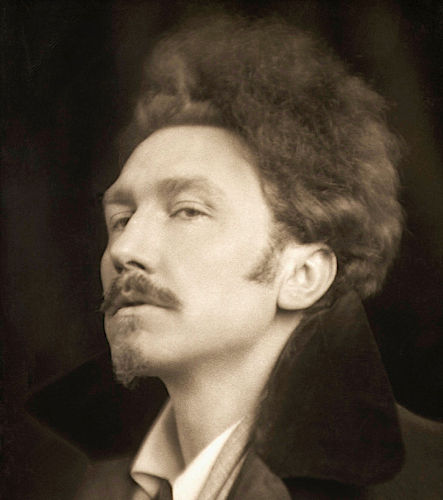

In 1901, at a Halloween party on the Penn campus, she met poet Ezra Pound (Pound attended the University of Pennsylvania from 1901 to 1903), then a handsome, muscular undergraduate with a mop of copper colored hair. Their relationship and eventual engagement flourished during Doolittle’s two-year tenure at Bryn Mawr College, until Pound abruptly ended the romance.

Doolittle later followed Pound first to New York, then to London, where she agreed to meet him on the steps of the British Museum in order to show him samples of her poetry. Pound admired the brevity and the easy rhythm of Doolittle’s verse, and helped launch her career as a poet.

In his amusing but cryptic essay on Doolittle in Prophets and Professors, author Bruce Bawer asks how Pound could build poetry reform with imagism around the works of a poet named Hilda Doolittle.

“So, before Pound tipped his hat and departed…that day, he scrawled something at the bottom of the manuscript of Hermes; H.D. Imagiste, Voila!’ The pathetic, pretentious and much-patronized Hilda was no more.”

But Pound abandoned H.D. again—this time as a poet and not a lover—when another poetic school (vorticism) caught his eye.

By this time, Doolittle, as H.D., was already published in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine and in Des Imagistes, the 1914 anthology of imagist poets.

Though intimate relationships between women were commonplace early in the 20th Century, women with lesbian inclinations were categorized as spinsters or pressured into heterosexual marriages. As a result, many women’s self-awareness of lesbian feelings usually occurred later in life. Doolittle’s own “discovery” was not actualized until after her 1913 marriage to poet Richard Aldington, which lasted several years.

In the 1920s, Doolittle met writer/filmmaker Winifred Ellerman, who used the pseudonym, Bryher. One of the richest women in England, Bryher supported Doolittle and provided her with a comfortable life so she could write.

The relationship between Bryher and Doolittle was more of a business relationship than a “marriage,” but Bryher’s love and commitment to Doolittle was the driving force behind a union that lasted 40 years. Bryher published several of Doolittle’s books, including her 1926 autobiographical novel,Palimpsest.

Though her novels were panned by critics as “slack and indulgent,” Doolittle’s work attracted the attention of T.S. Eliot and D.H. Lawrence. Her collected poems include: Hymen (1921); Heliodoroa (1924); and Red Roses for Bronze (1929).

Doolittle, however, chose not to publish her explicitly lesbian works during her lifetime. Pilate’s Wife, Asphodel and Hermione were published after her death in 1961.

In Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum you will find poet Marianne Moore’s Greenwich Village living room preserved in its original layout. Here, one can imagine what it must have been like when Moore, a friend of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and T.S. Eliot, began her routine of doing chin-ups.

Visit the Moore Room at the Rosenbach and you will see the metal chin-up bar in the poet’s reconstructed living room. You’ll also spot a 19th-Century settee and bureau, a footstool (a gift from T.S. Eliot) and a painting of a yellow rose by e.e. cummings.

Personal belongings aside, the details of Moore’s life remain as obscure as some of the meanings of her rhyming syllabic verse that the Cambridge Guide to Literature calls “marked by an unconventional but disciplined use of metrics, and a witty, often ironic tone.” Moore, like. H.D., had had taken fancies for a number of women in her life but she never went to the extent of calling herself a lesbian.

Moore’s mother, an extremely literate woman, didn’t understand her daughter’s cryptic poetry and was disappointed that this was the case.

Nowhere in the Cambridge Guide, or in Helen Vendler’s 528-page masterful critique of American poets, Voices and Visions, is anything stated about Moore’s romantic life although other sources maintain that Moore, like. H.D., had had taken a fancy to a number of women throughout her life although she never referred to herself a lesbian.

Moore was born in 1887 near Kirkwood, Missouri and lived with her maternal grandfather, John Warner Moore, who became an ordained minister in 1914. The family then moved to Carlisle and in 1916 to Chatham, New Jersey.

After graduating from Bryn Mawr College, a publisher told her that she should forget poetry and become a secretary. Moore followed the publisher’s advice for four years, though one of her works found its way into Harriet Monroe’s Poetry Magazine. Additional poems were published in Others Magazine. According to Vendler, these early poems echoed Moore’s concern that each work be part of a continuing effort to think through what poetry is. Though Moore would always examine painting, sculpture and decorative arts in her work—what Pound called “the logic of juxtaposition”—Vendler said that Moore’s way of writing became a search for identity.

Moore herself called most poetry “prose with a heightened consciousness.”

During most of her career, Moore condemned free verse, saying “it was the easiest thing in the world to create, with one intonation in the image of the other.”

In 1918, she moved with her mother to a basement apartment in St. Luke’s Place in Greenwich Village. The move was beneficial, since Moore believed that living in the city offered an “accessibility to experiences.” New York also radically expanded her ideas about poetry. What once had been a search for personal identity—she believed in Emerson’s dictum that “artistic imitation is suicide”—was transformed into a fascination for the world of trade and commerce. Because of commerce, Moore came to respect the values and inevitability of “influences.” T.S. Eliot’s collection of essays, Sacred Wood, also helped her see the value in the existing monuments of the past.

Moore’s first book of poems was published in 1921, her second, Observations, in 1924. In 1921, she began to write free verse (“The easiest thing in the world to create…”), and in 1926, she became editor of the prestigious literary magazine, The Dial. Her Collected Poems (1951) received the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

Throughout her life, Moore was a conservative Republican. As a conservative Republican it is doubtful whether she’d be a hot-in-demand commodity in Philadelphia’s over-the-top Leftist poetry circles were she somehow to return today and take up the pen.

Moore even voted for Herbert Hoover in 1928.

Before her death in 1972, Moore willed her literary and personal papers, as well as the contents of her living room, to the Rosenbach.