After writing and publishing two books on the homeless in Philadelphia (Learn To Do a Bad Thing Well: Looking For Johnny Bobbitt, and The Perils of Homelessness,both on Amazon), I’ve learned to keep an eye out for changes or trends in this area.

What changes have I noticed lately?

The homeless still come to the Kensington-Port Richmond area of the city for its cheap drugs. People still use heroin although for the most part heroin has been replaced by Fentanyl. There’s also Carfentanil, Cocaine and Methamphetamine. Meth seems to be the drug of choice among street connoisseurs, despite its terrible ingredients (battery acid, drain cleaner, and antifreeze). A user told me once that when Meth is injected you have to be very careful because if you shoot it incorrectly into a vein, or miss a vein entirely, you experience spasms of horrendous pain. There are also visible scars from these mistakes: large crusty boils often form on the skin.

The other drugs—K2, or synthetic marijuana—reduce people to blundering idiots in that they no longer walk or move the way normal human beings do. People on K2 can jerk and spasm violently, throwing themselves to the left and then to the right and often spinning themselves around in circles. And they do it quite out in the open: in parking lots, near convenience stores. They are mostly young men, some shockingly young. Their condition is so far gone they find it impossible to speak or form a coherent thought. They mouth words that mean nothing; there’s an inability to focus. Often, they fall to the ground in a heap. Quite a few of them wind up sleeping wherever they fall. In my neighborhood one can sometimes find them wrapped around a column under the nearby Rite Aid in the early morning hours. They resemble the war dead in some horrid disaster documentary.

Wandering men on drug safaris are everywhere in the city. Many are not recognizable as such because they are well dressed and conduct themselves normally.

“It’s very hard to be a woman living on the streets,” a forty plus year old woman told me one night on Aramingo Avenue while I was waiting for a bus. The woman, whose name was Victoria, was there with her street buddy, Mark, the brother of Keith, the homeless man I wrote about in these pages not long ago.

“It must be especially hard for a woman,” I replied. “Sleeping outside, waking up in the morning with no place to wash up, put on makeup or even brush your teeth.” Victoria agreed. “You have no idea. The winter is the worst time.”

Talking with Victoria made me think back to an incident in a nearby Dunkin Donuts when a good-looking homeless girl barricaded herself into the all- gender bathroom and began dying her hair. She was in the bathroom for quite some time and, when she finally emerged, a lot of the dye was still on her hair. The manager inspected the bathroom after the girl left and discovered great gobs of hair dye all over the sink and toilet. You can imagine the scene that followed.

Mark and Victoria, not a couple in the traditional sense, came to blows later when Mark discovered that Victoria went into his “stuff” and “borrowed a few things.” Those few things turned out to be items of value, including drugs. Their friendship ended almost as quickly as it had begun. This is the norm on the street. “You can’t trust anyone on the streets,” I’ve been told again and again. Even men who team up with other men, walking together everyday for weeks and weeks like old married couples, usually hit a wall when one of them does the other in.

“I nearly overdosed and fell asleep and he went into my knapsack and took my cellphone…”

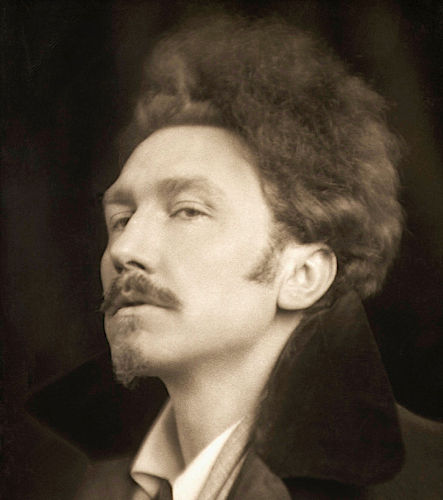

It’s an Ayn Rand world of every man or woman for himself. But if it’s not friends stealing from friends, it is strangers hiding along the streets where those in search of drugs go to “medicate.” Often these “hiders” are young teens who work in teams of two to five, sometimes more. They attack in packs like wolves because this gives them the advantage. They will attack the strongest of men, including the brooding strongman Justin, who came to Philadelphia from Lancaster about two years ago. (Justin, with his dark good looks, resembles a character out of a Genet novel.)

Two eager teens jumped Justin from behind, one stealing his small knapsack containing his cell phone and a large amount of drugs. Thinking Justin a pushover, they proceeded to pummel him when Justin turned into a prizefighter, swinging and doing heavy damage to one teen’s jaw. The frightened teen, pleading for mercy, was released and ran whimpering down a dark street.

A young man I interviewed for my Johnny Bobbitt book, Arno, can often be seen in my neighborhood. Sometimes he’s all-together, meaning standing straight and behaving normally, but at other times one can find him sitting curbside with his head lowered to the pavement. He disappears for long periods of time, which is typical of the homeless in the drug trade. Drug trade homeless transition from one neighborhood to another but generally they have one or two favorite neighborhoods where they will always revisit. Some will panhandle on Riverwards streets, only to travel to the Northeast to panhandle along the highly lucrative Roosevelt Blvd., and yet they always return to the Riverwards as if they were human Frisbees. The lucky ones hook up with people and find temporary shelter; some are arrested for drug offenses, while others do a stint in rehab. Most if not all resurface but some disappear forever.

I ran into Arno at my local Dollar Tree recently. He looked meticulously clean and all together, sporting a new jacket and a new attitude.

“Wow,” I said. “Good show. You look great.” I noticed a peculiar miniature Scotch patterned knapsack with lots of “lock down” straps over his left shoulder blade. I’d never seen such a tiny knapsack with so many straps. Ironically, just as I was thinking this, Arno began to explain how he was running drugs for a big-time pusher (or pushers).

“I have $5,000 worth of drugs in this little knapsack,” he said. “I run them to people and run the money back. If anything were to go wrong—if I lost the drugs or was robbed—I’d have to answer for it. It wouldn’t be good. It wouldn’t be nice. I’d be dead.”

There was Arno standing in the middle of Dollar Tree with $5,000 worth of drugs on his person. But who would suspect? With his bright innocent looking eyes and clean-cut demeanor, he looked like a Port Richmond mamma’s boy out on a family popcorn buying spree.

“Take care,” I said, “Be careful.”