I’ve collected a number of books over the

years. While my library is significant it could not be described as endless but

then again that description depends on who’s looking at it. Unlike some book

collectors, I don’t arrange my books alphabetically except for a few favorite

authors. I have a number of autographed books, but even these books tend to be scattered

among the many.

Lately I’ve had plenty of time to review the

contents of my library. I discovered that I still have books that I bought when

I was twenty years old and lived in Cambridge , Massachusetts Johnston Cambridge

I was

a big Anais Nin fan in the 1970s. Nin’s literary fans were mostly women who

also tended to keep diaries. Literary oriented males knew Nin primarily as one

of Henry Miller’s lovers (and financial supporters). When Anais Nin was

scheduled to speak in a church hall near Harvard I made sure that I was sitting

up front and center. I had just read her book, ‘The Novel of the Future,’ and her book of stories, Under a Glass Bell. Nin was famous for

her extraordinary book titles although I found her fiction too poetic and

abstract. Her stories lacked verve and nerve.

At

the Harvard lecture, Nin appeared onstage in a long cape, her distinctive voice

ringing out like a song bird. She spoke slowly, occasionally turning her head

in a slow motion fashion that reminded me of a wind up doll. Her famous

eyebrows, arched and dark penciled in to look like a sketch by Cocteau, could

be seen from the far end of the room. As I listened to her speak I couldn’t

help but imagine her making love to writer Henry Miller in Nin’s houseboat on

the Seine in Paris, ink wells and flower pots crashing to the floor as that

rake Miller put an end to the diarist’s delicacy.

This was the beginning of the feminist

era, when ardent feminists everywhere were proclaiming, “A woman needs a man

like a fish needs a bicycle.” (This was a lie because every feminist I knew

then seemed to have a skinny boyfriend). Nin attracted women who were more

literary than feminist but the feminists were out in force during that church

hall lecture. What I did not know then was that Nin’s lecture created some

controversy so that a symposium took place the following day in which Nin was asked to explain what she meant by this or

that statement. Years later, I was able to read the transcript of this interview

online and came away feeling amazed at how the interviewer failed to ruffle

Nin’s feathers. Nin seemed to have the

ability to take any vehement opposing view and work it to her advantage.

What I found most amusing then was the fact

that many women in the audience brought their own diaries to the lecture. Some

of the women were even dressed in capes but I don’t remember if any of them had

plucked or penciled- in their eyebrows.

The Boston-Cambridge area was intellectually

rich when it came to writers and artists.

In a

popular gay bar, Sporters on Cambridge Street Massachusetts General Hospital

who lived in the Boston

Sporters, located at the base of Beacon Hill , reflected the

bohemian accent of the Hill. It was a bar where everybody of all ages felt at

home; a bar where old gay men didn’t seem quite so isolated and “pathetic.” All

ages seemed to merge together in Sporters in a way that I haven’t seen before

or since. The bar had a democratizing air, especially when the jukebox played The Age of Aquarius from Hair.

Sporters attracted the likes of

Alan Helms, author of Young Man From the

Provinces: A Gay Life Before Stonewall, and a young lawyer named Dermont

Meagher, who would later become the first out judge in Boston

I knew both Helms and Meahger.

Meagher, intensely Irish looking, could have been a member of the Cape Cod

Kennedy clan. In Sporters, we would often share a beer and talk.

Helms, who had just moved to Boston New York Commonwealth Avenue

“Orgy at 119 Commonwealth Avenue

Open invitations like this meant that everyone who heard the call was

invited. These events attracted hundreds of men and were usually hosted by

wealthy Bostonians with immense townhouses so there was plenty of room for an

ever expanding crowd. At this particular orgy—my first and last—Helms and I sat

it out, observing the goings on with detached fascination. You can imagine my

surprise when, many years later, Helms made a lengthy reference to me in Young Man From the Provinces, even if he

labeled me an “artist” rather than a writer.

“In Boston Public Gardens New York Paris Boston

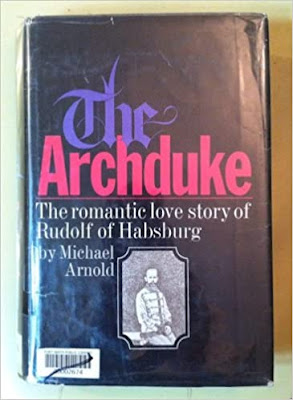

Arnold the novelist (not the famous Michael Arnold publishing currently)

was the size of Mozart, a petite man-boy with a page boy haircut who spent his

time in Sporters on a bar stool surrounded by adoring fans. His fans weren’t

especially literary types but I could see that they were well heeled men

focused on status and being seen with the right people, an unfortunate staple in

the gay world. Arnold

“The only way to be a writer is to make a

pot of coffee in the morning and then write for at least five hours,” he told me,

all the while taking long drags from his cigarette. Arnold Hollywood starlet, affected, caustic, with lots of “Oh darling’s” thrown in

for good measure. I enjoyed watching him

hold court, especially the way he’d flip his hair off his forehead while taking

those long cigarette drags.

Sporters, dingy looking but oh-so-terrific. The homeless man is misleading. Obviously this picture was taken just before the bar closed forever. There were no homeless people lounging around like this in 1971-72, etc. .

Sporters, dingy looking but oh-so-terrific. The homeless man is misleading. Obviously this picture was taken just before the bar closed forever. There were no homeless people lounging around like this in 1971-72, etc. .

I assured him that I had a good coffee pot before asking whether his

books ever dealt with homosexuality. When Arnold

“I don’t know what they know. I write for the market,” Arnold Provincetown Boston Provincetown

“So your books don’t go into gay issues at

all? There’s nothing…not even a hint of homosexuality? Not even the slightest

hint?”

“They are historical novels. My first novel

was reviewed by The New York Times. I

want my books to sell. If I were to write about homosexuality my books would

gather mold. Tell me about your work.”

What Arnold

I’ve Googled Michael Arnold’s name many

times over the years and have found nothing about him except references to his

first book and even fewer references to his second novel, both of which he made

sure I had a copies of. My guess is that Michael Arnold is no longer with us,

while Helms continues to write and live in Boston

Thom Nickels

Contributing Editor