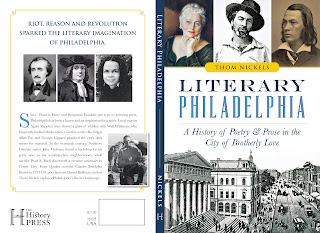

THE LOCAL LENS

THOM

NICKELS

The City of Philadelphia Philadelphia Alabama New York Hunter College Harlem as a young girl, then

studied for a while at New York University San Francisco State

In

2011, the 77 year old poet, teacher and activist Philadelphia Philadelphia Philadelphia

With poem titles like “I Still Have Keys to the Apartment,” “Bran Muffins

Have Nothing to Do With it! So There!” and “Leaving the Only Bed in America

That Keeps Me Satisfied,” Conrad’s irreverent style might not go over at the

city’s Union League but his cult following is symbolic of poetry’s status in

the city. The “new style” Philadelphia Pittsburgh Republic of South Vietnam Crimson River

Another great Philadelphia North Philadelphia , who was ordained a priest by John

Cardinal O’Hara in 1959. Fr. McNamee, who has spent most of his priesthood

serving the poor and disadvantaged, is credited with bringing Dorothy Day’s

Catholic Worker movement to Philadelphia Villanova University Northern Ireland Philadelphia

While the mystical poems of a priest might

not be ideal to represent the City of Philadelphia ,

a secular mystic poet like Leonard Gontarek, the recipient of five Pushcart

Prize nominations. Like the Philly poet Jim Cory, author of a number of books

and chapbooks and editor of the 1997 Black Sparrow Press edition of James

Broughton’s poems, Packing Up For

Paradise, Gontarek’s Wallace Stevens

insurance salesman look means that neither he nor Cory would be

“recognized” as poets in the street, at least if one is going by the “uniform”

of younger urban poets which tends towards affectation, such as the arrangement

of neck scarves. This style can range

from the minimalist placement of one scarf to the piling on of two or three so

that one thinks of café habitués in Paris

or of certain Middle Eastern revolutionaries. While the poetic uniform is

usually relegated to the young—consider prose writer George Lippard’s

flamboyant dress—other poets seem happier to blend with the scenery much the

same way that Walt Whitman, who dressed as if he was a farmer, blended in with

his Camden townsfolk.

Jim Cory believes that poetry can be different

things to different people at different times, and he told me that when he was

12 he stumbled on The Mentor

Book of Major American Poets on

the paperback rack at the Stamford Museum Nature Center

Philadelphia’s most famous modern poet, who almost always wore a suit

and tie, was the 1973-1974 Poet Laureate of the United States, Daniel Hoffman.

Hoffman’s poetry is almost always just a little sad, but it is also noted for

its joy in the small things of life. As he once told an interviewer, “Even when

a poet writes about something negative the fact that he puts it into a form

controls it, makes it positive.” The

author of more than 25 books moved to Philadelphia Philadelphia New

York City University of Pennsylvania

Blunt to a fault, Hoffman said that he

wouldn’t want students like this in his class, even though he expressed

sensitivity towards the pitfalls of being a 17 year old beginning poet, for

whom all poetry generally means, “my

love affair.” Young poets of this caliber, Hoffman explains, all write “the

same verbal spaghetti without any control or form,” all the more reason to make

them “read good poetry. ”One teaching method he used to cure the “my love

affair” view of poetry was to copy out police reports and have the students

choose one and then write a poem about why the culprit was arrested. This

exercise was important, he says, to

get the students “out of themselves.”

Born in 1923, Hoffman died on March 30, 2013 in Haverford , Pennsylvania

French poet

Arthur Rimbaud’s line, “You must change your life,” set the tone for Philadelphia

In many ways, Philadelphia Moore Boston New England .

While living in Philadelphia , Moore published The Ramadan Sonnets (Jusoor/City Lights), and in 2002, The Blind Beekeeper (Jusoor/Syracuse University

Press). San Francisco poet, playwright and novelist Michael McClure has

written that Moore’s poems are like Frank O’Hara’s, where “there are no boundaries or limits to

possible subject matter,” and where “imagination runs rampant and it

glides.”

Moore is not a

poet of empty things and ideas but aspects of the spiritual as the divine seem

to invade every word he writes. He was

viewed as legendary in the California of the 1960s, in part because he was able

to be “spiritual” without losing his sense of humor. He is the spiritual poet with a comedic

wink.

Moore works with Larry Robin at Philadelphia’s

Moonstone Arts Center where he helps coordinate Moonstone’s annual Poetry Ink

readings of 100 Poets. In 2011, 2012 and 2014 he was

awarded the Nazim Hikmet Prize for Poetry, and in 2013 he won an American Book

Award.

In this age of ongoing dialogue among

Muslims, Christians and Jews, the sacred person known as the Virgin Mary, mentioned some thirty-four

times in the Koran. The sacred person concept is not lost on Moore, who writes

in Five Short Meditations on the Virgin Mary:

I saw Mary board a

bus at Broad and State

her head covered and her face radiant

her head covered and her face radiant

small and held

within herself

careful and preoccupied

careful and preoccupied

interior moisture

her preferred cloister

the bus passengers sudden ghosts before her

the bus passengers sudden ghosts before her

her shoes small and

tattered

her hands carrying a book

her hands carrying a book

If any had spoken

to her she might have become lost

If she had spoken

to anyone

they might have become saved

they might have become saved